Independence in Kraków

Why Kraków? Because it was the first significant Polish city to achieve independence. Emperor Franz Joseph’s successor, Charles I, exerted every effort to preserve the crumbling edifice of the Dual Monarchy, later dismissed by Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński as a “putrid patchwork of nations”. On 16 October 1918, in a final, desperate attempt to avoid the inevitable, the Emperor issued a declaration transforming the Habsburg Empire into a Bund freier Voelker (Union of free Nations). However, it was far too late, as the constituent nations of the Empire were already striving for independence and ignoring Vienna.

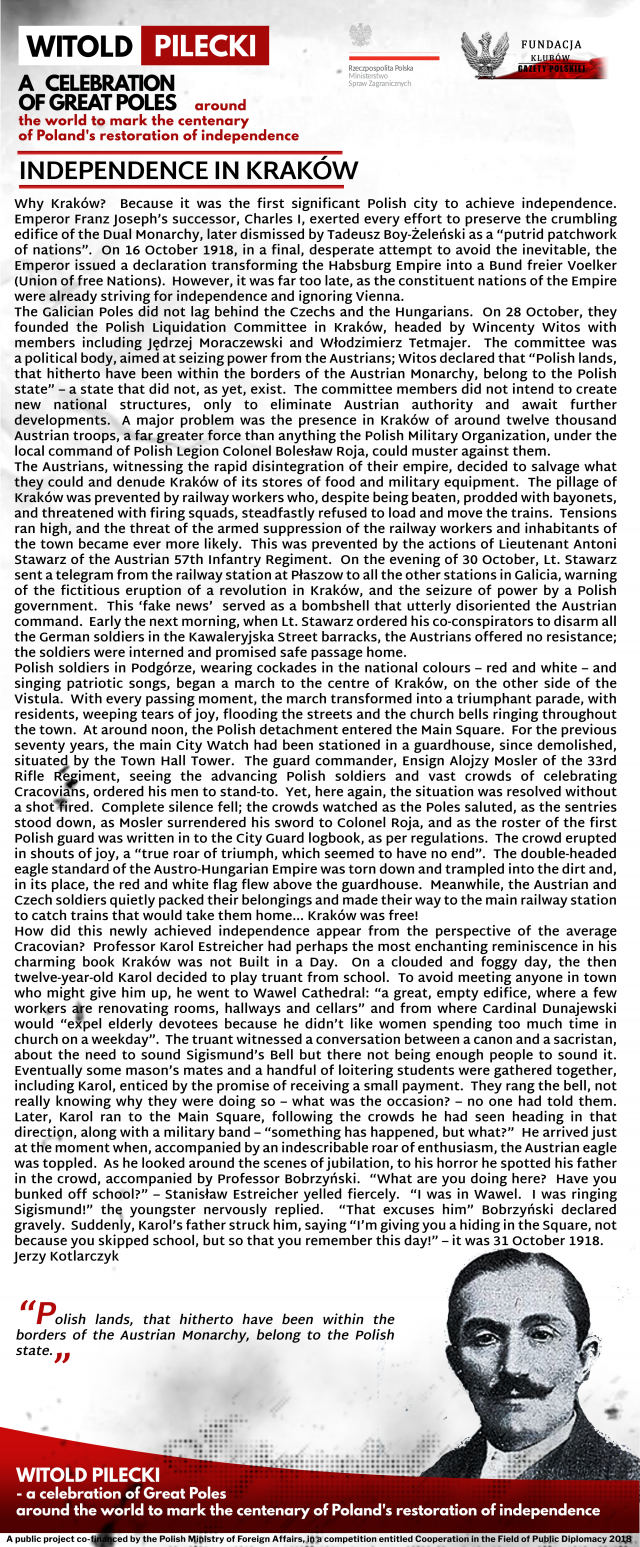

The Galician Poles did not lag behind the Czechs and the Hungarians. On 28 October, they founded the Polish Liquidation Committee in Kraków, headed by Wincenty Witos with members including Jędrzej Moraczewski and Włodzimierz Tetmajer. The committee was a political body, aimed at seizing power from the Austrians; Witos declared that “Polish lands, that hitherto have been within the borders of the Austrian Monarchy, belong to the Polish state” – a state that did not, as yet, exist. The committee members did not intend to create new national structures, only to eliminate Austrian authority and await further developments. A major problem was the presence in Kraków of around twelve thousand Austrian troops, a far greater force than anything the Polish Military Organization, under the local command of Polish Legion Colonel Bolesław Roja, could muster against them.

The Austrians, witnessing the rapid disintegration of their empire, decided to salvage what they could and denude Kraków of its stores of food and military equipment. The pillage of Kraków was prevented by railway workers who, despite being beaten, prodded with bayonets, and threatened with firing squads, steadfastly refused to load and move the trains. Tensions ran high, and the threat of the armed suppression of the railway workers and inhabitants of the town became ever more likely. This was prevented by the actions of Lieutenant Antoni Stawarz of the Austrian 57th Infantry Regiment. On the evening of 30 October, Lt. Stawarz sent a telegram from the railway station at Płaszow to all the other stations in Galicia, warning of the fictitious eruption of a revolution in Kraków, and the seizure of power by a Polish government. This ‘fake news’ served as a bombshell that utterly disoriented the Austrian command. Early the next morning, when Lt. Stawarz ordered his co-conspirators to disarm all the German soldiers in the Kawaleryjska Street barracks, the Austrians offered no resistance; the soldiers were interned and promised safe passage home.

Polish soldiers in Podgórze, wearing cockades in the national colours – red and white – and singing patriotic songs, began a march to the centre of Kraków, on the other side of the Vistula. With every passing moment, the march transformed into a triumphant parade, with residents, weeping tears of joy, flooding the streets and the church bells ringing throughout the town. At around noon, the Polish detachment entered the Main Square. For the previous seventy years, the main City Watch had been stationed in a guardhouse, since demolished, situated by the Town Hall Tower. The guard commander, Ensign Alojzy Mosler of the 33rd Rifle Regiment, seeing the advancing Polish soldiers and vast crowds of celebrating Cracovians, ordered his men to stand-to. Yet, here again, the situation was resolved without a shot fired. Complete silence fell; the crowds watched as the Poles saluted, as the sentries stood down, as Mosler surrendered his sword to Colonel Roja, and as the roster of the first Polish guard was written in to the City Guard logbook, as per regulations. The crowd erupted in shouts of joy, a “true roar of triumph, which seemed to have no end”. The double-headed eagle standard of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was torn down and trampled into the dirt and, in its place, the red and white flag flew above the guardhouse. Meanwhile, the Austrian and Czech soldiers quietly packed their belongings and made their way to the main railway station to catch trains that would take them home… Kraków was free!

How did this newly achieved independence appear from the perspective of the average Cracovian? Professor Karol Estreicher had perhaps the most enchanting reminiscence in his charming book Kraków was not Built in a Day. On a clouded and foggy day, the then twelve-year-old Karol decided to play truant from school. To avoid meeting anyone in town who might give him up, he went to Wawel Cathedral: “a great, empty edifice, where a few workers are renovating rooms, hallways and cellars” and from where Cardinal Dunajewski would “expel elderly devotees because he didn’t like women spending too much time in church on a weekday”. The truant witnessed a conversation between a canon and a sacristan, about the need to sound Sigismund’s Bell but there not being enough people to sound it. Eventually some mason’s mates and a handful of loitering students were gathered together, including Karol, enticed by the promise of receiving a small payment. They rang the bell, not really knowing why they were doing so – what was the occasion? – no one had told them. Later, Karol ran to the Main Square, following the crowds he had seen heading in that direction, along with a military band – “something has happened, but what?” He arrived just at the moment when, accompanied by an indescribable roar of enthusiasm, the Austrian eagle was toppled. As he looked around the scenes of jubilation, to his horror he spotted his father in the crowd, accompanied by Professor Bobrzyński. “What are you doing here? Have you bunked off school?” – Stanisław Estreicher yelled fiercely. “I was in Wawel. I was ringing Sigismund!” the youngster nervously replied. “That excuses him” Bobrzyński declared gravely. Suddenly, Karol’s father struck him, saying “I’m giving you a hiding in the Square, not because you skipped school, but so that you remember this day!” – it was 31 October 1918.

Jerzy Kotlarczyk

- Pierwsza warta polska na odwachu krakowskim. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Pierwsza warta polska na odwachu krakowskim. ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Pierwsza warta polska na odwachu krakowskim. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Pierwsza warta polska na odwachu krakowskim. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Wincenty Witos. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Wincenty Witos. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Bolesław Roja. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Jędrzej Moraczewski. Ze zbiorów Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego

- Popiersie Wincentego Witosa w Parku Jordana w Krakowie (Foto. Fundacja Klubów „Gazety Polskiej”)

- Popiersie Wincentego Witosa w Parku Jordana w Krakowie (Foto. Fundacja Klubów „Gazety Polskiej”)